Episode 7: Aeolus

The “Aeolus” episode, with its newspaper headlines, represents the first of many chapters where Joyce pushes the boundaries of the novel as a form. Can a novel contain newspaper headlines? Is a novel still a novel if ⅕ th of it is written as a play? What if it also contains a catechism? How do these devices alter the reading experience?

Joyce saw all forms of language - from Dublin slang to Deuteronomy, from pop music lyrics to Virgil’s Eclogues, from advertising slogans to Shakespeare - as fodder for the great project of Ulysses. In the case of this episode’s headlines (which Joyce added to the text at proof stage) we immediately notice their effect of simultaneously interrupting and framing the prose and narration.

In the schema, Joyce identified the lungs as the organ for this chapter; indeed, the episode features lots of comings and goings (inhales and exhales), and the diction is suffused with references to air and wind. In terms of the correspondence to Homer, the episode is named for Aeolus, the keeper of the winds, who gives Odysseus a magical sack of winds; appropriately, this chapter is filled with the hot air of political speeches, rhetorical devices, and the inflated prose of newspapers and newspapermen. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew have nearly returned home - they can even see men tending fires on the shores of Ithaca. Relieved, and exhausted from sailing for two-weeks straight, Odysseus takes a power nap. While he’s sleeping, Odysseus’s men jealously assume that the sack of winds contains riches, gripe about unfair distribution of wealth, and open the bag, letting loose the winds and blowing the ship all the way back to Aeolus’s island. In correspondence to this frustrating moment in The Odyssey, the “Aeolus” episode includes a few near-misses as Bloom attempts to do his job as an advertising agent; likewise, Mr. Bloom and Stephen just miss an encounter in the newspaper offices.

By noon, the funeral-goers have returned from Glasnevin Cemetery (likely by way of Dunphy’s pub) to the center of Dublin, where Mr. Bloom gets right to work on placing an advertisement for House of Keyes teashop in the Evening Telegraph newspaper. He meets first with Red Murray, who cuts out an older ad for Keyes, which Mr. Bloom then takes to the foreman, Nannetti. In addition to working in the press, Nannetti is also a city councillor tipped to become Lord Mayor of Dublin (he will indeed do so in 1906). In Nannetti’s office, Bloom finds Hynes submitting his piece about Dignam’s funeral. Hynes owes Bloom three shillings from three weeks ago, and Bloom gives a subtle hint to that effect by informing Hynes that the cashier is about to head to lunch…maybe try to catch him? And maybe pay me back with what you get paid? Hynes doesn’t bite.

Bloom tactfully explains to Nannetti his idea for the art – two keys crossed inside a circle – to be added to the Keyes ad. This imagery suggests the Manx parliament on the Isle of Man, representing a form of home rule and therefore independence from Britain. Thus, Mr. Bloom’s idea for the ad makes a faint political statement. Mr. Bloom has seen a design for the art in a Kilkenny newspaper, which he could get at the National Library. Nannetti likes the idea and agrees to run the ad if Keyes gives the paper a renewal of three months. So, Mr. Bloom has a deal to broker.

Bloom’s mind returns to the encounter with Menton at the end of the “Hades” episode, and, like George Costanza in the “jerk store” episode of Seinfeld, he thinks he should have said, after Menton popped out the dent in the hat, something like “Looks as good as new now” (7.173). So very human of Bloom to re-play and revise a moment of social tension from earlier in the day.

Amid the din of the printing press, Bloom thinks about the way inanimate objects make sounds that resemble words. Bloom also lingers to marvel at the speed of the typesetter laying out the letters backwards. The text of the novel reads “mangiD kcirtaP” in imitation of the way the type would be laid, but, of course, the letters themselves would also be backwards (e.g., a “b” would look like “d”). For all of its clever inventiveness, this little moment demonstrates the text’s limitations in representing exactly what Joyce is trying to do. Without question, Ulysses pushes the boundaries of what written language can represent to a reader, ranging from pointed yet lyrical narration, pitch-perfect dialogue, and exquisite description to the silent discourse of an individual’s consciousness and, later in the book, the fleeting and irrational fantasies of the subconscious.

Keyes’s teahouse is in Ballsbridge, a southeastern suburb of Dublin, and Bloom smartly decides to call the shop before heading down there on a tram to make sure Mr. Keyes himself is on the premises. He heads to the office where the telephone is. He also moves the lemon soap back from his breast to his hip pocket, the smell of the soap reminds him of Martha Clifford’s question about what perfume his wife wears, which prompts him to consider popping home to see Molly before her encounter with Boylan, but he decides against it.

Bloom enters the office of the Evening Telegraph to find Simon Dedalus, Myles Crawford, Ned Lambert, and a man called professor MacHugh laughing at the terribly inflated language of Dan Dawson’s speech given the previous day, which was published in the paper that morning, and which was discussed in the funeral carriage earlier. J. J. O’Molloy, a failing lawyer, enters the office and is greeted by the other men. We might notice that Bloom received no such greeting.

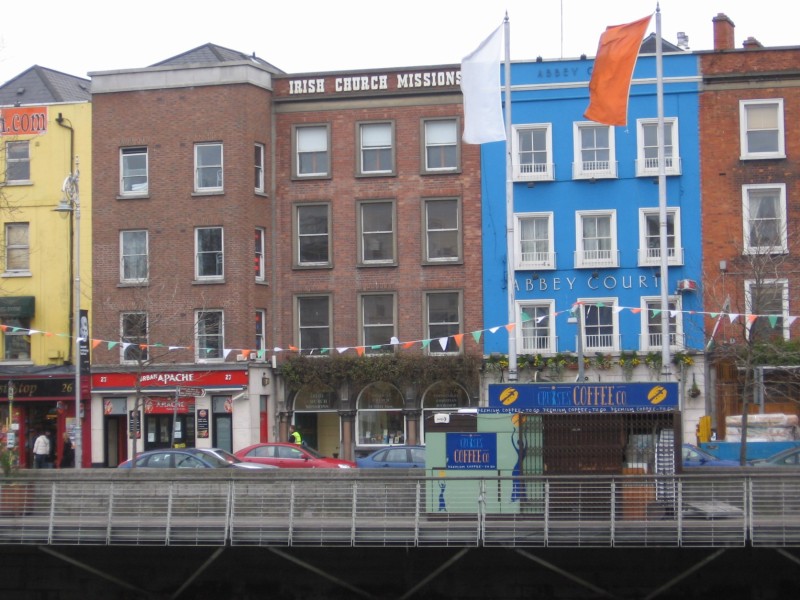

The Oval Pub, which remains today and serves good Irish stew.

Simon Dedalus prompts an excursion with Ned Lambert to The Oval pub just down the street. Myles Crawford and the professor remain behind, and Bloom asks to use the phone. A man named Lenehan (seen in the Dubliners story “Two Gallants”) enters, offering his pick for the Gold Cup (Sceptre). We overhear Bloom’s side of the call to Keyes – Mr. Keyes has stepped out of the shop to go to Dillon’s auction house, which happens to be just around the corner from the newspaper offices. Bloom, in a rush to catch Keyes and save himself the trip to Ballsbridge, pops out of the office and collides with Lenehan, who makes a bit of a scene. Bloom tells Crawford where he’s going (he’s subtly hinting: I’ll need your final approval for this ad, so please don’t leave before I return) and hurries off, followed by newsboys mocking his walk behind him.

Bachelor's Walk, where Dillon's Auction House was located in 1904.

Crawford suggests they all go to meet Simon and Ned at The Oval, the professor begins a meditation on empire. The British Empire is compared unfavorably to the Roman Empire, and Roman culture is compared unfavorably to Jewish culture. Lenehan demands silence (and does not receive it) for his new riddle (“what opera resembles a railwayline?” (7.512) – the answer will be The Rose of Castille). Stephen Dedalus enters with O’Madden Burke to deliver Mr. Deasy’s letter on foot & mouth disease.

With Stephen’s arrival, we now have access to his inner monologue for the first time since we left him at the end of “Proteus.” Careful readers will remember that he tore off a bit of Deasy’s letter to compose a few lines of poetry on the rocks of Sandymount strand – Mr. Crawford notices the tear, and Stephen mentally recites the quatrain he wrote. Stephen is slightly embarrassed to serve as courier for Garrett Deasy, but he has fulfilled his promise. We might observe here an echo of Bloom’s inserting M’Coy’s name into the list of funeral attendees in the previous episode; both Stephen and Bloom honor small but somewhat unpleasant commitments.

The men in the office discuss Deasy and his wife, who it’s clear is a difficult woman and from whom Mr. Deasy is now separated. Perhaps this information explains some of Deasy’s misogyny in the “Nestor” episode? The men also wistfully discuss Irish history, we see a few other inner echoes from Stephen’s morning, and Lenehan again presses to offer and answer his riddle. (a quick aside here: in a fantasy in the “Circe” episode later in the novel, Bloom will deliver this same riddle, and he will be condemned as a plagiarist…but Bloom is not present for either of Lenehan’s deliveries of this riddle here in “Aeolus.” Did Joyce make a - gasp - mistake?)

There’s a celebration of all the diverse talent present in the room (which is slightly absurd, because J. J. O’Malloy is a failing lawyer, professor MacHugh is not actually a professor, Stephen is to this point an unsuccessful poet, and Lenehan is, well, yappy). The professor adds Bloom to the list as a representative of “the gentle art of advertising” (7.608), and Burke suggests Molly’s talent for singing, which draws a laugh from Lenehan, who we might assume sees Molly principally for other of her “talents.”

A statue of James Joyce, located near the site of Mooney's pub.

Crawford directly implores Stephen to write for the newspaper and uses the work of Ignatius Gallaher (a character from the Dubliners story “A Little Cloud”) as an exemplar of journalistic excellence. In the middle of Crawford’s explanation of a particular piece Gallaher wrote about the Phoenix Park murders, Mr. Bloom calls back to the office from Dillon’s. Bloom is trying to close the deal with Keyes but needs Crawford’s approval for the negotiated terms. When MacHugh tells Crawford that Bloom is on the phone, the editor says “tell him to go to hell” (7.672) and continues speaking to Stephen. Stephen, for his part, is distracted from Crawford’s exposition by his own mental editing of the poem he started that morning. He is not interested in the world of journalism. As his mind wanders to Hamlet, he offers a valid query: if King Hamlet was asleep when Claudius poisoned him, how did he know who did it?

The other men ask Stephen his opinion of A. E. and the theosophy crowd, and they report that A. E. told an American interviewer something about Stephen. Insecure as ever, Stephen desperately wants to know what was said but refrains from asking.

MacHugh raises a new topic: a speech he heard by John F. Taylor about the revival of the Irish language, which he lauds as one of the best displays of oratory he has ever heard. From memory, he goes on to recite the speech, which metaphorically identifies England as Egypt and Ireland as Israel.

The remaining facade of Mooney's Pub.

Stephen, on his payday, offers to stand a round of drinks, and the other men respond with enthusiasm. (Remember that Stephen was supposed to stand rounds for Mulligan at The Ship at 12:30? That didn’t happen; Stephen sent a telegram saying he wasn’t going to make it.) Lenehan suggests Mooney’s, a pub just down the street. Crawford agrees to publish Deasy’s letter. As the group leaves the offices, Stephen begins to tell a story that seems like a first draft of a Dubliners short story in its depiction of an anticlimactic slice of everyday life. The men enter the street on their way to the pub and encounter a panting Mr. Bloom, who, because Crawford refused his phone call, has had to hustle from Dillon’s. Keyes has countered with a two month renewal (Nannetti had asked for three), and Bloom wants to know whether the paper will accept this deal. Crawford tells Bloom to tell Keyes to kiss his arse. Bloom, recognizing that the group is off for a drink (and specifically recognizing “careless” (7.987) Stephen as the ringleader), wisely realizes that he is unlikely to get his way by standing between Crawford and a pint. He offers just to work up the design. Crawford improves on his earlier reply: Keyes can kiss his royal Irish arse.

As the men continue their walk down the street, Stephen resumes his story of the two women and their plums climbing to the top of Nelson Pillar and spitting out the pits. As he finishes, he is celebrated as a new Antisthenes.

Nelson’s Pillar “in the heart of the Hibernian Metropolis.” (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)