Episode 15: “Circe”

Ok, this one’s a doozy. Beginning shortly before midnight, the “Circe” episode uses the form of a play to portray a kaleidoscopic blend of real and imaginary happenings over the course of an hour in Dublin’s brothel district. “Circe” takes up nearly 150 pages in the Gabler edition of Ulysses, making it about as long as the first eight episodes of the novel combined.

Worried over Stephen’s drunken condition, Bloom has followed him into Nighttown in hopes of taking care of him. Between the end of “Oxen” and the start of “Circe,” a sundering occurred between Stephen and Buck Mulligan in Westland Row Station; perhaps Buck simply abandoned Stephen, or maybe there was a physical confrontation. Regardless, Buck and Haines have departed without Stephen on the last train toward the Tower in Sandycove. As Stephen anticipated all the way back in “Telemachus,” he will not sleep there tonight. Buck has usurped his place. Accompanied by Lynch (and trailed by Bloom), Stephen has taken the train from Westland Row to Amiens Station and is now on his way to a brothel. Bloom is hustling to catch up after stopping briefly to buy snacks.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew land on Aeaea, and a team of scouts discover the palace of Circe, a witch goddess. Circe invites Odysseus’s men inside for a drink and then magically turns them into pigs. One man escapes to tell Odysseus about their comrades’ fate and Circe’s trickery. Odysseus bravely hopes to rescue his men from Circe’s enchantment; on the way to her house, Odysseus receives help from Hermes, who offers him a plan and equips him with moly, a magical herb that will protect him from Circe’s witchcraft. The plan works: the moly counters Circe’s magic, she swoons for Odysseus and transforms his crew from pigs back into men. Odysseus and Circe then make love. For a year. Finally, some of Odysseus’s crew shake him from the madness of his long Circean interlude and compel him to resume the journey home to Ithaca.

In early spring 1920, Joyce emerged from the 1,000 hours he had spent writing “Oxen” and turned his attention to “Circe.” He expected that this episode, like the few he had recently composed, would take him two to three months to complete. Little did he know that “Circe” would require eight drafts and take over half a year to write (Letters), much less that it would have the power to bewitch his creative process and entirely transform Ulysses. This episode, with its exhaustive reprises of virtually every character, object, and idea introduced in the novel thus far, would compel Joyce to revise much of what he had previously written. Joyce estimated that he wrote a third of Ulysses at the proof stage of the revision process (Beach 58), arranging codependent details all over the novel and weaving a web of intratextual puzzles that will “keep the professors busy for centuries” (JJ 521).

In addition to the power of “Circe” to transform the novel, this episode also portrays the grotesque transformation of hundreds of characters (dead and living), inanimate objects, and concepts thus far encountered in Ulysses. During the composition of this episode, Joyce drafted as a reference a “pair of notesheets […] where Joyce listed all the ‘characters’ that had appeared thus far in Ulysses to assure their inclusion in ‘Circe’” (Groden 175). This list also includes concepts like parallax and topics of conversation from earlier in the novel that Joyce intended to reprise. As David Hayman puts it, “Joyce seems to have taken the whole book, jumbled it together in a giant mixer and then rearranged its elements in a monster pantomime” (Hayman 102). The episode’s dramatic entertainment is often hilarious in its expressiveness, wit, and hyperbole, but it also has moments of monstrous darkness.

We’ve previously seen glimpses of each of the magical spells cast by “Circe” elsewhere in the novel, such as Stephen’s haunting memories in “Telemachus,” Mr. Bloom’s exotic reveries in “Calypso,” the extensive lists and exaggerations of “Cyclops,” Buck’s brief play in “Scylla & Charybdis,” the flamboyant narrative style of “Sirens,” as well as the personality ascribed to inanimate objects and animals, such as Bloom’s cat in “Calypso,” the boots in “Sirens,” and the gulls in “Lestrygonians.” That said, whereas these impulses are suppressed in the novel to this point, the “Circe” episode allows for their unrestrained expression. As Karen Lawrence puts it, “‘Circe’ provides a stage for a libidinous release of tendencies in the language and in the characters” (Lawrence 150-51).

The performance gives center stage to the subconscious in a series of seven major fantasies. Indeed, imaginary events dominate the episode’s content, accounting for roughly 90% of its text (Kenner, “Circe” 347). These fantasies may be split-second flights of imagination in the character’s mind, yet some of them require dozens of pages to be faithfully represented. Some of these daymares consume the conscious attention of Bloom or Stephen and distract them from external reality. Others may be purely textual flourishes inserted by the Arranger without basis in the characters’ psyches. The episode’s shifting between these different modes of fantastic expression is disorienting and difficult to follow. David Hayman explains that “though the major hallucinatory sequences are carefully set off […], the arranger makes no clear distinction between minor hallucinations and the normal surface” (Hayman 102). Furthermore, as Karen Lawrence explains, “this confusion is compounded, of course, by the fact that most of the dramas in which the characters participate are composite dramas that recombine elements from the book’s past, transgressing the boundaries of the psyches of the characters” (Lawrence 161). In these ways, “Circe” will always resist rational analysis and clear explanation, but I endeavor to guide you through the dark magic of this episode.

The red-light district of Marseille (not Dublin) around the turn of the century. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com, a truly astonishing resource curated by Aida Yared of Vanderbilt University)

If you thought that a visit to the brothel district was going to be fun and sexy, the “Circe” episode’s opening stage directions quickly dispel you of that notion by establishing the unseemly setting of Joyce’s Nighttown. The tracks are “skeleton,” the signals warn of “danger,” the houses are “grimy,” the men are “stunted,” and the women “squabble” (15.2, 3, 5). Indeed, Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1885 labeled this part of Dublin “the worst slum in Europe” (JJ 367). Located in east Dublin between Montgomery Street and Tyrone (né Mecklenburgh) Street, Nighttown is an ugly place filled with unsavory people.

You’ll remember Cissy Caffrey from the “Nausicaa” episode, and you might wonder what she’s doing here at this hour of night. She’s hanging out with two crude British soldiers, Private Carr and Private Compton, who will feature prominently in the final scene of the episode. The redcoats mock Stephen as “the parson” (15.64) – he’s still wearing his widebrimmed hat – as he and Lynch slip past on their way to the brothel. Lynch was first introduced in A Portrait as a university friend of Stephen’s, and Father Conmee caught this young man emerging from the bushes with a young woman back in “Wandering Rocks.” You’ll remember him drinking and teasing Stephen in “Oxen.” Here in “Circe,” he is described as having “a sneer of discontent wrinkling his face” (15.75). He and Stephen ignore the solicitation of an elderly bawd with “snaggletusks” (15.78) as Stephen speaks Latin from the Catholic Mass. They pass Edy Boardman (also from “Nausicaa”) “bickering” (15.90) about another woman, and Lynch kicks at a stray dog.

Lynch notes the absurdity of Stephen spouting “metaphysics in Mecklenburg street” (15.109) and inquires as to which brothel they are going. Stephen is hoping to see Georgina Johnson, the prostitute on whom Stephen spent the money A.E. loaned him for food (see 9.195). Stephen strikes a pose, and you might notice the prominence of his ashplant walking stick in the stage directions thus far and when Lynch tells him to “take your crutch and walk” (15.130). A drunk navvy (a term for a manual laborer) fires a snot rocket.

The Caffrey twins from “Nausicaa” appear and climb a lamppost. You may be thinking, okay, maybe Cissy Caffrey and Edy Boardman are here, but no way are two four-year-old boys running around the red-light district at midnight. Probably not, but we can’t be entirely sure about anything in this foggy episode. As you read, you’ll be tempted to wonder whether a moment in “Circe” is imaginary or real, and I’ll do my best to differentiate between the two in this guide, but I’ll also suggest that you may find it more interesting or productive to inquire into the literary effect of those uncertain moments. As the Arranger impishly combines and warps the novel’s elements in this episode, try to allow yourself to be affected by these absurdities as you will – “Circe” is a performance, after all.

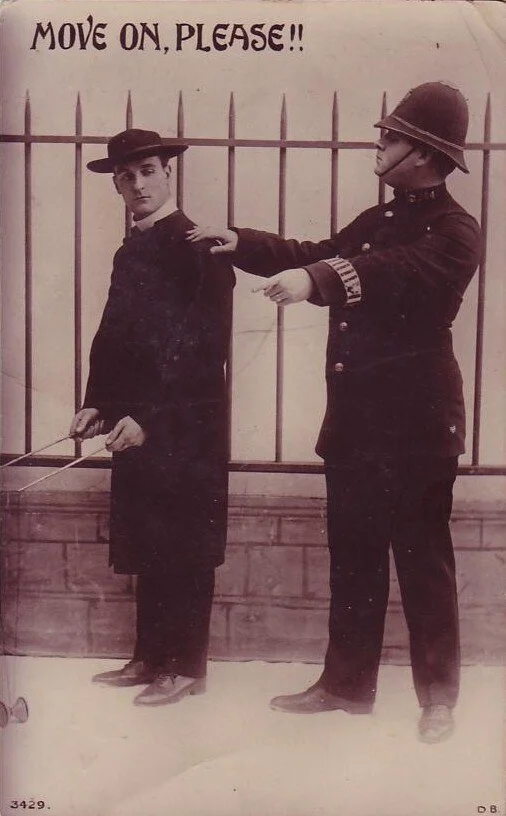

From amid hazy “snakes of river fog” (15.138), Mr. Bloom emerges with snacks and “flushed, panting” (15.142-43) from hustling to catch up to Stephen. He is a few minutes behind, as we can tell from him passing “Antonio Rabaiotti’s” ice cream cart, which we first saw “halted” (15.5) as Stephen and Lynch walked past at the outset of the episode. Bloom stops again to buy some street meat and suffers from a stitch in his side. He notes a glow south of the river and realizes that there is a fire, a “big blaze” that might engulf “his [Blazes’] house” (15.171). Realizing that he’ll lose Stephen if he doesn’t “Run. Quick” (15.174), he crosses the street and is nearly struck by passing cyclists. He is then nearly run over by “a dragon sandstrewer” (15.185). Bloom raises “a policeman’s whitegloved hand” (15.190-91) to signal stop; clearly, Bloom does not instantaneously put on a white glove to direct traffic, so this is the first instance of the Arranger augmenting reality. The motorman slams on the brake and is “thrown forward” (15.192). He curses Bloom, who nimbly “trickleaps to the curbstone” (15.196). This is pretty funny stuff.

It is worth noting Bloom’s characteristic pragmatism in response to these close calls; he thinks he should resume Sandow’s exercises and considers expanding his insurance coverage to include street accidents. Notice also that the bicycle bells and motorman’s footgong have speaking parts in the play. Back in the “Aeolus” episode, Bloom remarked in his inner monologue that “everything speaks in its own way” (7.177); the “Circe” episode pushes this thought to an extreme, giving voice to everything, including inanimate objects, characters who aren’t actually present, dead people, and animals.

A brief encounter with a “sinister figure” (15.212) in a sombrero guarding the entrance to Nighttown is the first of the episode’s imagination-embellished events we can locate in Bloom’s mind. He is clearly feeling some measure of discomfort as a married man in this part of town, and his muttered suggestion that the figure is a “Gaelic league spy” (15.220) sent by the Citizen from “Cyclops” conveys the paranoia and trauma that Bloom is carrying from the clash in Barney Kiernan’s a few hours earlier. Then, Bloom’s slapstick encounter with the ragsackman exemplifies how quickly the tone and register of this episode can shift. Little Jacky and Tommy Caffrey collide with Bloom, and, thinking they might be pickpockets, he quickly checks the inventory of his pockets. Searching for the reality in all this, I suppose that Bloom noticed a person leaning against the wall (but he did not speak to this person (certainly not in Spanish)), his path was momentarily obstructed by a man carrying a sack across his shoulders (but they don’t leap left and right in unison), and somebody short accidentally bumps into him (but it wasn’t the Caffrey twins).

The episode’s first sustained fantasy occurring entirely in a character’s psyche begins with the appearance of Bloom’s father Rudolph. Rudolph scolds his son for his imprudence with money, for being in Nighttown, for leaving Judaism (which seems unfair since Rudolph himself converted to the Church of Ireland), and for running with the wrong crowd once or twice back in high school. Bloom’s mother, a gentile, appears and dramatically laments the corruption of her son. Clearly, Bloom is wrestling with loads of guilt here.

In terms of how these fantasies reveal guilty memories buried deeply within the character’s subconscious, you may recall a passage from “Oxen of the Sun” predicting this aspect of the “Circe” episode: “There are sins or (let us call them as the world calls them) evil memories which are hidden away by man in the darkest places of the heart but they abide there and wait. […] Yet a chance word will call them forth suddenly and they will rise up to confront him in the most various circumstances, a vision or a dream” (14.1344-50). As suggested in “Oxen,” a simple word or thoughtless gesture in reality can trigger a significant psychological event in this episode.

Bloom’s feelings of meek shame continue as a domineering Molly appears, demanding to be called “Mrs. Marion” (15.306), just as Boylan addressed his letter to her this morning (see 4.245). She is wearing the Turkish attire she wore in Bloom’s dream last night, as he recalled toward the end of “Nausicaa”: “She had red slippers on. Turkish. Wore the breeches” (13.1240-41). In this fantasy, Molly/Marion is clearly wearing the pants in the relationship. She is accompanied by a turbaned camel, who plucks for her a mango and bows subserviently. Bloom also “stoops his back” (15.323) and stutters deferentially before Molly/Marion seems to imply that she is pregnant, presumably with Boylan’s child.

In an illustrative moment, the language of Molly’s exclamation of “Nebrakada! Femininum!” (15.319) is taken from the book of secret prayers/spells Stephen thumbed through in the “Wandering Rocks” episode before Dilly interrupted him (see 10.849). The fact that a figure in Bloom’s mind borrows language from Stephen’s day exemplifies the impossibility of pinning “Circe” down. As Hugh Kenner states, “however we try to rationalize ‘Circe’ there are elements that escape. It is the second narrator’s justification and triumph, an artifact that cannot be analyzed into any save literary constituents” (Kenner, Voices, 92). In short, the Arranger has the entire text at his disposal, and he is recycling its language into “Circe” as a new, unexpected, irrational, and evocative work of literature that is in some ways distinct from the rest of Ulysses while being entirely dependent upon it.

The guilt Bloom feels for not fulfilling his role as a husband continues as he explains to Molly/Marion that he failed to pick up her lotion from Sweny’s. Then the bar of lemon soap speaks a couplet in tetrameter before Sweny’s face “appears in the disc of the soapsun” (15.340-41) and announces Bloom’s bill from this morning. Molly/Marion speaks lines from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Bloom again wonders whether she is pronouncing the Italian correctly, and she “saunters away” (15.352), signaling the end of this first extended fantasy.

We momentarily snap back to reality with the unpleasant image of an elderly bawd with “the bristles of her chinmole glittering” (15.357) as she peddles a virgin. This is the same woman who previously solicited Stephen and Lynch. Then, the prostitute with whom Bloom had his first sexual encounter, Bridie Kelly, briefly appears (probably not really, although I do think Bloom sees her at the end of “Sirens” as well as in the upcoming “Eumaeus” episode).

Think Bloom and Josie. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

The next extended fantasy begins with Gerty MacDowell expressing contempt (and then love) for Bloom and his behavior on the strand in “Nausicaa.” Then Josie Breen, Bloom’s ex, appears and shames him for being “down here in the haunts of sin” (15.394). Bloom offers disjointed denials, explanations, pleasantries, and flattery. Josie threatens to tell Molly that she caught him in Nighttown, but Bloom suggests that Molly is attracted to the taboo. The Bohee brothers appear and perform their banjo minstrel show (which is full of racist imagery and stereotypes). Bloom, “always a favourite with the ladies” (15.448), tries to charm Mrs. Breen. Costume changes and histrionics ensue. Denis Breen appears with the HELY’S sandwichboards, and the text seems to suggest that Alf Bergan is the author of the U.p: up. postcard. Josie warms to Bloom, who acts scandalized by her advances and tries out the Leah alibi that he will later use with Molly. His mentioning of supper introduces Richie Goulding and the Ormond Hotel restaurant waiter Pat from “Sirens” into the fantasy. The navvy we have seen earlier in the episode gores Goulding with his “flaming pronghorn” (15.514), and Bloom suggests that he is a spy.

The fantasy returns to Bloom’s conversation with Mrs. Breen who calls B.S. on the Leah story, and Bloom asks her to walk on for more confidential conversation. She agrees, and he asks her to recall in vivid detail an outing they shared 14 some-odd years ago to watch horseraces. It seems like Bloom and Josie had some sort of connection that day, but, after a series of seven yeses, she fades away and the fantasy ends before the memory reaches its climax.

Our return to the reality of Nighttown is again revolting as “a standing woman, bent forward, her feet apart, pisses cowily” (15.578-79). Sheesh. The cast of loiterers, whores, the navvy, and the redcoats sing and shout. A passage of Bloom’s inner monologue reveals his sense that chasing Stephen is a “wildgoose chase” (15.635), that he’s tipsy on only two drinks, that he’s hoping to look after Stephen and his money, that he was saved from the sandstrewer by his “presence of mind” (15.644), and that Molly once drew a penis on a frosted carriagepane. He passes by whores smoking cigarettes, and the Arranger imagines the wreaths of “sicksweet weed” smoke reprising a line from the “Sirens” episode: “Sweet are the sweets. Sweets of sin” (15.655, 11.156). Charitable Bloom feeds the meat he just purchased to the dog that has appeared (and changed breeds) throughout the episode.

The watch. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

Two police of the night watch approach Bloom, and in his paranoid imagination they accuse him of committing a public nuisance. He protests that he is “doing good to others” (15.682) by feeding the dog and, presumably, by trying to take care of Stephen. The gulls he fed in “Lestrygonians” return to serve as character witnesses to his benevolence. Poor Bob Doran appears and falls off his barstool into oblivion. The watch ask for his name and address, and he tells them he is “Dr Bloom, Leopold, dental surgeon” (15.721) – there really was a Dr. Bloom practicing dentistry in Dublin in 1904. They ask for proof, and the Henry Flower card falls out of his hatband. When pressed, he produces the yellow flower Martha Clifford sent him. He gets chummy with the watch and poses as a gallant. Martha Clifford appears and uses language heard in “Sirens” from the song “Martha” in the opera M’appari. When the watch begins to arrest Bloom, he claims “mistaken identity” (15.760) and inverts Martin Cunningham’s statement in “Hades” that it is “better for ninetynine guilty to escape than for one innocent person to be wrongfully condemned” (6.474-75) into the self-serving “better one guilty escape than ninetynine wrongfully condemned” (15.763). When Martha accuses Bloom of being a “heartless flirt” (15.767), the fantasy becomes a trial.

Bloom first poses as a Britisher, citing his father-in-law’s service and claiming that he, too, fought in the Boer War. Next, he presents himself as a writer of fiction; Miles Crawford from “Aeolus” and Philip Beaufoy, author of the story Bloom read in the outhouse in “Calypso,” appear as witnesses. Beaufoy accuses Bloom of plagiarism and of “leading a quadruple existence” (15.853-54). Mary Driscoll, the Blooms’ former housekeeper, then takes the witness stand against Mr. Bloom and accuses him of assault. Bloom “mumbles incoherently” (15.923). Under the direction of Professor MacHugh from the pressroom in “Aeolus,” a “crossexamination proceeds re Bloom and the bucket (15.929) – it seems that Bloom once emergency-pooped in a plasterer’s bucket he found on the street. My god.

Bloom is defended in this trial by J.J. O’Molloy, the talented but down-on-his-luck lawyer who we’ve seen in “Aeolus,” “Wandering Rocks,” and “Cyclops.” O’Molloy claims that Bloom is an infant and his approach to Mary Driscoll was “brought on by hallucination” (15.945). Unconvincingly, he claims that Bloom made “no attempt at carnally knowing” Ms. Driscoll, then argues that “intimacy did not occur,” and finally offers that Bloom did not repeat his solicitations toward her (15.947-49). To me, all of this implies that he did make inappropriate advances toward Mary Driscoll.

O’Molloy goes on to claim that Bloom is simple minded (and Bloom performs as such), that a conspiratorial “hidden hand” (15.975) is acting against Bloom, who is “the last man in the world to do anything ungentlemanly” (15.977). Dlugacz and the Zionist Agendath Netaim investment prospectus are recalled from “Calypso.” In the end, O’Molloy pleads that the court give Bloom the “benefit of the doubt” (15.1004). Bloom cites a few former employers and landlords as references, but then he lies again about his day. A parade of three high class women then accuse Bloom of improper advances. Mrs. Bellingham claims that Bloom once complimented her as a “Venus in furs” (15.1046), which is the title of a novel by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, from whose name masochism is derived (Gifford 466). Along these lines, Bloom implored Mrs. Talboys “to chastise him as he richly deserves, […] to give him a most vicious horsewhipping” (15.1070-73). More on Bloom’s masochism later, but as you have likely already gathered from the two fantasies we’ve seen thus far, Bloom is subconsciously craving punishment for his various failures, misbehaviors, and flaws.

As the focus shifts away from Bloom’s ogling and toward his cuckolding, the text gives voice to the quoits of the Bloom’s bed, which we also heard as a trilling note in the musical “Sirens” episode. The jury box reveals a jury of Bloom’s peers – men he has encountered over the course of the day, including the Nameless One, the narrator of the “Cyclops” episode. The Nameless One conflates Boylan’s affair with Molly with the tension over Bloom’s presumed winning of a “hundred shillings to five” (15.1149) by betting on Throwaway in the Gold Cup. The second watch levels a slew of other wild accusations against Bloom, Long John Fanning (the subsheriff from the “Wandering Rocks” episode) appears and arranges for Bloom to be hung by H. Rumbold, whose letter we saw back in “Cyclops” (see 12.415-31).

The bells toll for thee, Bloom, signaling doom and echoing the “Heigho! Heigho!” of St. George’s churchbells in “Calypso.” Bloom offers a final sputtering defense of his own character and appeals to Joe Hynes (who still owes him three shillings) for support. Hynes “coldly” (15.1195) denies him. We begin to circle back to the impetus for this fantasy (the police seeing Bloom lay down the parcel of meat for the dog) as the second watch claims it was a bomb. Bloom explains that the package contained pig’s feet and that he attended a funeral. The text exhumes Paddy Dignam to validate Bloom’s claim. When Dignam “worms down” (15.1255) to the underworld, he is followed by the huge rat that caught Bloom’s attention in “Hades.” Tom Rochford, who we learned in “Wandering Rocks” saved a man who fell down a manhole, dives after Dignam to save him, too. The fantasy recedes as kisses materialize in the air and “flutter upon” (15.1275) Bloom, who hears “a piano sound” (15.1268) inside a brothel. This “sad music” (15.1278) makes him think he’s perhaps found Stephen. He’s right.

We return to reality as Zoe Higgins “accosts” (15.1281) Bloom and points him into the brothel run by Mrs. Cohen, who is “on the job herself tonight” (15.1288). Zoe asks if Bloom is Stephen’s father on account of both men wearing black; we know that Bloom is a father in search of a son, and Stephen is a son in search of an adequate father figure, but a whorehouse is an unlikely location for this heralded atonement to occur. That’s Ulysses for you. Zoe’s wandering hands entice Bloom, and, searching for his nuts, she finds his mother’s potato “talisman” (15.1313) in his pocket and keeps it. In another description that takes the sexy out of Nighttown, “she bites his ear gently with little goldstopped teeth, sending on him a cloying breath of stale garlic” (15.1339-40). Yuck. But Bloom’s “awkward hand” (15.1343) gets interested in Zoe nonetheless. She asks if he has a cigarette, and he lectures her about smoking before suggesting that “the mouth can be better engaged than with a cylinder of rank weed” (15.1350-51). Zoe’s invitation to “make a stump speech out of it” (15.1353) sends Bloom’s imagination into a prolonged fantasy of his political rise and fall. The bells of nearby churches chime midnight.

This third extended fantasy taps into Bloom’s deep desire for approval and his closely held aspirations as a social reformer and civic problem-solver. After delivering his “stump speech” on tobacco and the ills of “public life” (15.1361), Bloom is named Lord Mayor of Dublin, celebrated by a “torchlight procession” (15.1373) and congratulated by high profile individuals. Bloom delivers a garbled yet passionate speech on machines (which seems to repackage his vacillations back in “Hades”: “Couldn’t they invent something automatic so that the wheel itself much handier? Well but that fellow would lose his job then? Well but then another fellow would get a job making the new invention?” (6.176-79)). A triumphal parade follows, and Bloom is anointed “Leopold the First” (15.1473).

In a universally transmitted decree, Bloom drops Molly for “the princess Selene” (15.1506-07), a spouse more worthy of his high station. John Howard Parnell proclaims Bloom the “successor to [his] famous brother” (15.1513-14), meaning Charles Stewart Parnell, the late leader of the Irish nationalist movement. Bloom announces “the new Bloomusalem” (15.1544), and construction begins on “a colossal edifice with crystal roof, built in the shape of a huge pork kidney, containing forty thousand rooms” (15.1548-49). Bloom’s ascendancy is not without destruction or casualties.

The man in the brown macintosh from Dignam’s funeral appears and casts doubt on Bloom, claiming “his real name is Higgins” (15.1562), which was Bloom’s mother’s maiden name (and Zoe’s last name, coincidentally). Bloom orders the man in the macintosh shot, and he disappears. Other enemies die, including graziers – remember that Bloom was fired from his job at Cuffe’s for “giving lip to a grazier” (12.837-38). Women and children shower Bloom with adoration, and he gregariously makes the rounds. Hynes finally offers to repay the three shillings he owes Bloom, which Bloom magnanimously refuses to accept. Even the Citizen is “choked with emotion” (15.1617) and moved to tears by his love for Bloom.

Think the goddess statues Bloom examined in the National Museum. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

Bloom speaks what little Hebrew/Yiddish words he knows, and the gibberish is translated into an announcement of Bloom’s offering of “free medical and legal advice” (15.1630). The following Q&A is pretty funny. Larry O’Rourke, the publican around the corner from the Blooms’ home, offers a gift of “a dozen of stout for the missus” (15.1674-75), which Bloom refuses. Above reproach, Bloom “stand[s] for the reform of municipal morals” and for “the union of all” (15.1685-86). Continuing to play the hits, the Arranger reprises Davy Byrne’s yawn onomatopoeia from “Lestrygonians”: “Iiiiiiiiiaaaaaaach!” (15.1697, 8.970). The statues of goddesses are carted in, presumably for Bloom’s inspection (thwarted as it was by Buck Mulligan in “Scylla & Charybdis”). As “all agree with” Bloom’s “schemes for social regeneration” (15.1702-03), we see the depth of Bloom’s desire for acceptance in this fantasy of widespread and enthusiastic appreciation for his ideas.

Father Farley, a Jesuit who refused to admit Molly into a church choir years ago (perhaps because of Bloom being a Freemason), condemns Bloom as “an anythingarian seeking to overthrow our holy faith” (15.1712-13). Dante Riordan, to whom Bloom sought to ingratiate himself in hopes of receiving something in her will, curses him much like she cursed Parnell in A Portrait. Bloom is also cursed by Mother Grogan, a bawdy character from an Irish folk song.

Against this upbraiding, Bloom tells the Rose of Castile/Rows of Cast Steel joke Lenehan told back in “Aeolus”; Lenehan appears and accuses Bloom of being a “plagiarist” (15.1734). However, Bloom had already left the newspaper offices to find Mr. Keyes (see 7.436) when Lenehan told this joke (see 7.591). This discrepancy is either a mistake by Joyce (unlikely) or a demonstration of the Arranger’s mischievous bending of the text in this episode.

In any event, the fantasy twists to a conflict between Bloomites and antiBloomites (we all must pick a side!). Bloom blames Henry Flower, his “double” (15.1770) for the debauchery and hypocrisy of which he is accused. He calls on the doctors and medical students from “Oxen” to testify on his behalf. Mulligan diagnoses Bloom as “bisexually abnormal” (15.1775-76), and Dixon calls him “a finished example of the new womanly man” (15.1798-99). Joyce here seems to be playing with Otto Weininger’s 1903 pseudoscientific book Sex and Character, which argued that all people possessed both male and female “plasms” on a cellular level, and the relative balance of these plasms within an individual contributed to a sliding scale of gender performance (Byrnes 268). Along these lines, Bloom is revealed to be pregnant and “so want[s] to be a mother” (15.1817). Mrs. Thornton, the midwife who delivered Milly and Rudy, helps Bloom give birth to male octuplets who go on to be attractive, cultured, and prominent men. Again, Bloom’s fantasies in “Circe” exaggerate his various subconscious desires, guilts, and fears, here emphasizing his unsatisfied dream of raising a successful son. Also interesting to note: one of Bloom’s sons is named Chrysostomos, the novel’s first word accessed in Stephen’s inner monologue all the way back in “Telemachus” (see 1.26).

Challenged to perform a miracle, Bloom offers eleven amazing feats, the last of which, “eclips[ing] the sun by extending his little finger” (15.1850-51), he already performed once today in the “Lestrygonians” episode (see 8.566). Then, Bloom is renamed Emmanuel and placed at the end of an absurd messianic lineage. But Bloom is no messiah, and he clearly has some shameful moments to account for, as implied by a crab, a female infant, and a hollybush. The tide turns against Bloom, “all the people cast soft pantomime stones at Bloom” (15.1902), and even his old friends Mastiansky and Citron “wag their beards” (15.1905) and decry Bloom as a false Messiah. Two other Jews, Mesias the tailor and Reuben J. Dodd appear. Then Bloom is set on fire. The Citizen approves.

Bloom becomes a martyr, and the grieving Daughters of Erin offer a Bloomian version of the Litany of Mary with Ulysses inside jokes followed by the epiphora “pray for us.” The third extended fantasy concludes with “a choir of six hundred voices” (15.1953) singing Handel’s “Alleluia”.

Reality returns, and we realize that Zoe is just finishing the retort she began back at line 1353: “Go on. Make a stump speech out of it. […] Talk away till you’re black in the face” (15.1353, 1958). Literally no time has passed during these 17 pages of fantasy.

Zoe brings Bloom into the brothel, and Bloom seems poised to secure her services for a “short time” (15.1985). Bloom expresses a thought of Molly, which Zoe assuages and “lur[es] him to doom” (15.2012-13). Zoe seems unappealing with “the odour of her armpits” and “the lion reek of all the male brutes that have possessed her” (15.2015, 2017), yet these scents draw Bloom into the musicroom. He enters “awkwardly” (15.2023) and “averts his face” (15.2038) from a departing john in a “purple shirt and grey trousers” (15.2035). We see Lynch, Kitty, Stephen, and Florry. Stephen drunkenly pontificates about music. Lynch mocks and teases Stephen. Florry suggests that “the last day is coming this summer” (15.2129), which sends Stephen’s mind into an apocalyptic vision of a hideous, manic hobgoblin playing roulette with planets, revealing Stephen’s thoughts on the callous or even malevolent force controlling the universe. In another of the Arranger’s manipulations of the text, Stephen’s mind borrows language from the snippet of theosophical dialogue Bloom overheard A. E. saying to Lizzie Twigg as they passed him on bicycles in “Lestrygonians” (see 8.520). The evangelist preacher advertised in the “Elijah is coming” (see 8.13) flyer sermonizes. The time is now 12:25 am. The men from the Holles Street Maternity Hospital become “the eight beatitudes” (15.2237), and the men from the National Library also appear. In reality, Zoe adjusts the gasjet on the chandelier and lights a cigarette. Lynch uses a poker to lift her slip and reveal that she is going commando.

Think Zoe. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

The fourth extended fantasy begins as Bloom’s grandfather Lipoti Virag appears and leads Bloom through an enthusiastic and authoritative appraisal of the three whores. Zoe isn’t wearing underwear, garments for which Bloom has a fetish; Kitty is too skinny and is feigning sadness; Florry is attractively plump, but Bloom is put off by the stye on her eye. (note the pun on “stye” – Circe transformed Odysseus’s men into pigs). Virag, like Bloom, is an armchair scientist and suggests remedies for the stye. Bloom claims “it has been an unusually fatiguing day, a chapter of accidents” (15.2380). Indeed.

Virag inspires Bloom toward assertiveness and encourages him to “stop twirling your thumbs and have a good old thunk” (15.2382-83) with one of the prostitutes. He ridicules Bloom for previous plans and ambitions left unfulfilled: “you intended to devote an entire year to the study of the religious problem and the summer months of 1886 to square the circle and win that million” (15.1399-401). As we have seen all day, Bloom has curiosities and interests in wideranging topics, but his mind is fairly content to leave questions unanswered (or half-answered). Bloom expresses some paradoxical musings on his current place in the past and the possibilities of the present future. A moth circles around a light, Virag discusses aphrodisiacs, and female anatomy is worried over. Suave Henry Flower appears and sings a song while playing the guitar.

The focalization returns to Stephen at the pianola, and his inner monologue first thinks of his dad and then turns to another inadequate father figure, Mr. Deasy. Stephen thinks of sending “old Deasy” a telegraph, which he mentally sketches: “Our interview of this morning has left on me a deep impression. Though our ages. Will write fully tomorrow. I’m partially drunk, by the way” (15.2497-99). Hilarious.

Almidano Artifoni, Stephen’s Italian voice teacher who expressed fatherly concern for Stephen in the “Wandering Rocks” episode, then appears. His words of advice and encouragement (see 10.344-51) are warped into “you ruin everything” (Gifford 496). Florry asks Stephen to sing, but he refuses. Stephen’s mind splits into Philip Sober, who scolds him for his drinking and wasting money, and Philip Drunk, who tries to remember the person who he previously discussed Swinburne with in the brothel. Stephen is too drunk to sing, and the Philips mock him.

Zoe claims that a priest recently visited Mrs. Cohen’s but couldn’t ejaculate. Virag, still present in Bloom’s mind, offers anti-Catholic ideas regarding the corruption of priests. The text flits back and forth between fantasy and reality, and Virag becomes increasingly unhinged until he finally “unscrews his head” (15.1636) and exits. The two Philips adapt language from Stephen’s inner monologue from “Proteus,” and then Kitty’s head of “winsome curls” (15.1586) recall the narrative style of “Nausicaa.” An animalistic Ben Dollard is described in terms reminiscent of the gigantism of the “Cyclops” episode as he sings and is adored by the virgin nurses from “Oxen.” Henry Flower strums a lute and sings the “Martha” song from “Sirens” while “caressing on his breast a severed female head” (15.2620). Crazy shit.

Florry, more right than she could know, calls Stephen “a spoiled priest” (15.2649). Lynch pushes the joke, claiming that Stephen is “a cardinal’s son” (15.2651), which brings to Stephen’s mind Simon, “primate” (15.2654) of Ireland, reciting verses and being swarmed by midges. Another john comes down the stairs after a visit with Bella Cohen to retrieve his coat and hat before leaving the brothel. Bloom passes around the chocolate he purchased prior to the start of the episode and wonders if perhaps the man is Boylan, paying for sex because his affair with Molly didn’t come off…or maybe he’s doing “the double event” (15.2706). He relaxes when the man departs into the night. Accepting his chocolate back from Zoe, he takes a bite and thinks about aphrodisiacs. He seems to have been convinced by his grandfather to satisfy himself with a prostitute.

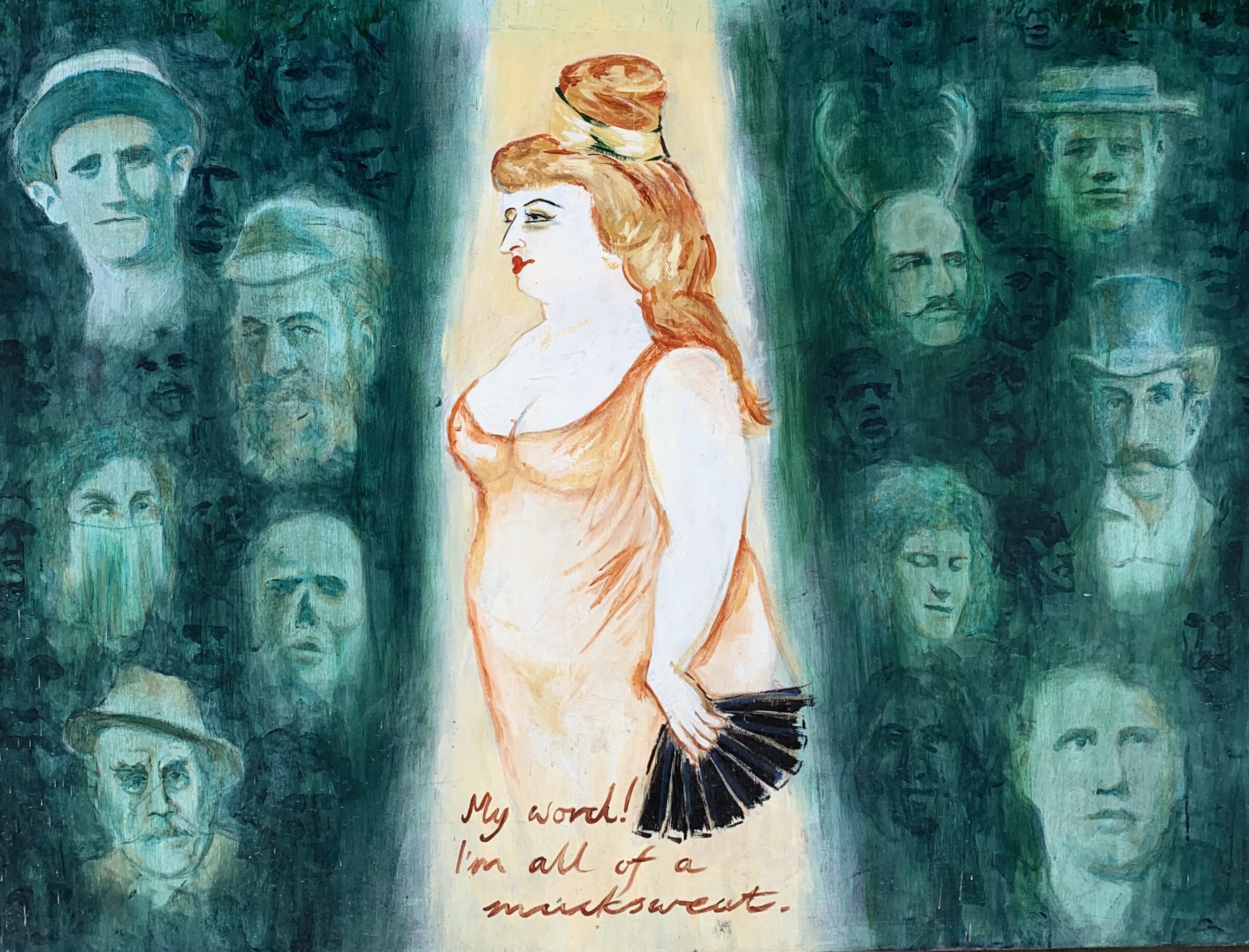

Then Bella Cohen enters. She is described as a “massive whoremistress” with a “sprouting moustache” on her “olive face”; she is wearing a fringed threequarter-length ivory gown and using a fan to cool herself from her recent exertions (15.2742-47). She vulgarly announces that she’s “all of a mucksweat” (15.2750) and makes eye contact with Bloom. This begins the episode’s climactic fifth fantasy. As Stanley Sultan describes, this daymare confronts Bloom’s shame over his failure to be the man Molly needs and presents the imperative for him to put an end to his perverse behaviors (Sultan 322).

In reality, Bloom doesn’t seem to interact with Bella Cohen until line 3480, some 22 pages after she first looks at him; in fact, he doesn’t really interact with Bella in the fantasy, either – the text portrays him in conversation with The Fan, The Hoof, and Bello, but not Bella. Joyce’s use of synecdoche here manipulates the basic understanding readers have about figurative language: rather than the part representing the whole, the part itself is personified and invested with agency, as demonstrated by Bloom’s conversation with The Fan, which establishes Bloom’s masochistic desire for domination. The Hoof then takes the fantasy to the next level by threatening violence while Bloom laces its boot. Bella becomes Bello, and Bloom’s pronoun changes to “her” (15.2847). This gender bending recalls the Weiningerian gender theory mentioned earlier. Bloom seems pleased to be reduced and defiled. Without Moly, our Ulysses is transformed into a pig “on all fours, grunting, snuffling, rooting at [Bello’s] feet” (15.2852-53).

As Bello grinds his heel into Bloom’s neck and promises to “shame it out of [him]” (15.2868), we might note that “his craving for punishment so extremely represented in the fantasy derives from guilt rather than sexual perversion” (Sultan 316). Bloom tries to hide, and the other whores intercede on “her” behalf. Bello sits on him and smokes a cigar while reading the paper, twisting Bloom’s arm and slapping “her” face. The other whores now join in Bello’s domination of Bloom. The Ascot Gold Cup pops up again as Bello reads the result in the paper, curses the “outsider Throwaway” and “quenches his cigar angrily on Bloom’s ear” (15.2936-37). Bello begins to ride Bloom like a horse, squeezes Bloom’s “testicles roughly” (15.2945), and “farts stoutly” (15.2958-59) on “her.” If Bloom was craving punishment, “what [he] longed for has come to pass” (15.2964-65).

The fantasy moves from physical violence to an accounting of “the sins of the past” (15.3027). Bloom twice wore Molly’s undergarments and posed for himself in the mirror. He offered Molly in ads written on the walls of five public bathrooms. He “presented himself indecently” (15.3031) among other things. Bloom is now in Bello’s servitude, forced to drink piss. Bello plans to pimp “her” out as the brothel’s “new attraction” (15.3083). Bello then speaks of Bloom like cattle at an auction.

Bello asks if Bloom can “do a man’s job” (15.3132), to which Bloom begins to reply “Eccles street” (15.3134) before Bello alludes to Boylan as “a man of brawn in possession there” (15.3137). Bloom has been usurped, and Bello claims that Boylan has impregnated Molly. In a disjointed series of pleading exclamations (“To drive me mad! Moll! I forgot! Forgive! Moll …. We …. Still ….” (15.3151), Bloom attempts to piece together his mental anguish, his neglectful forgetting of his duties as a husband, his desire for Molly’s forgiveness, and his belief in the possible redemption of their marriage. Bello “ruthlessly” (15.3153) quashes these thoughts.

Then, like the Ghost of Christmas Past, Bello prompts Bloom to return to see what he recognizes as the party at which he first met Molly, but Bello is messing with him; the woman he sees is his daughter Milly with Bannon. Bello continues to manipulate Bloom’s mind, suggesting that Bloom’s most treasured household items will be defiled. Bloom seems to be turning a corner from a desire for punishment to a desire to “return” (15.3191) and redeem what he has lost.

The Nymph from the framed picture in the Bloom’s bedroom appears to comfort Bloom and thank him for rescuing her from the pages of the softcore porn magazine Photo Bits. However, the Nymph has also been scandalized by what she has seen and heard in the Blooms’ bedroom.

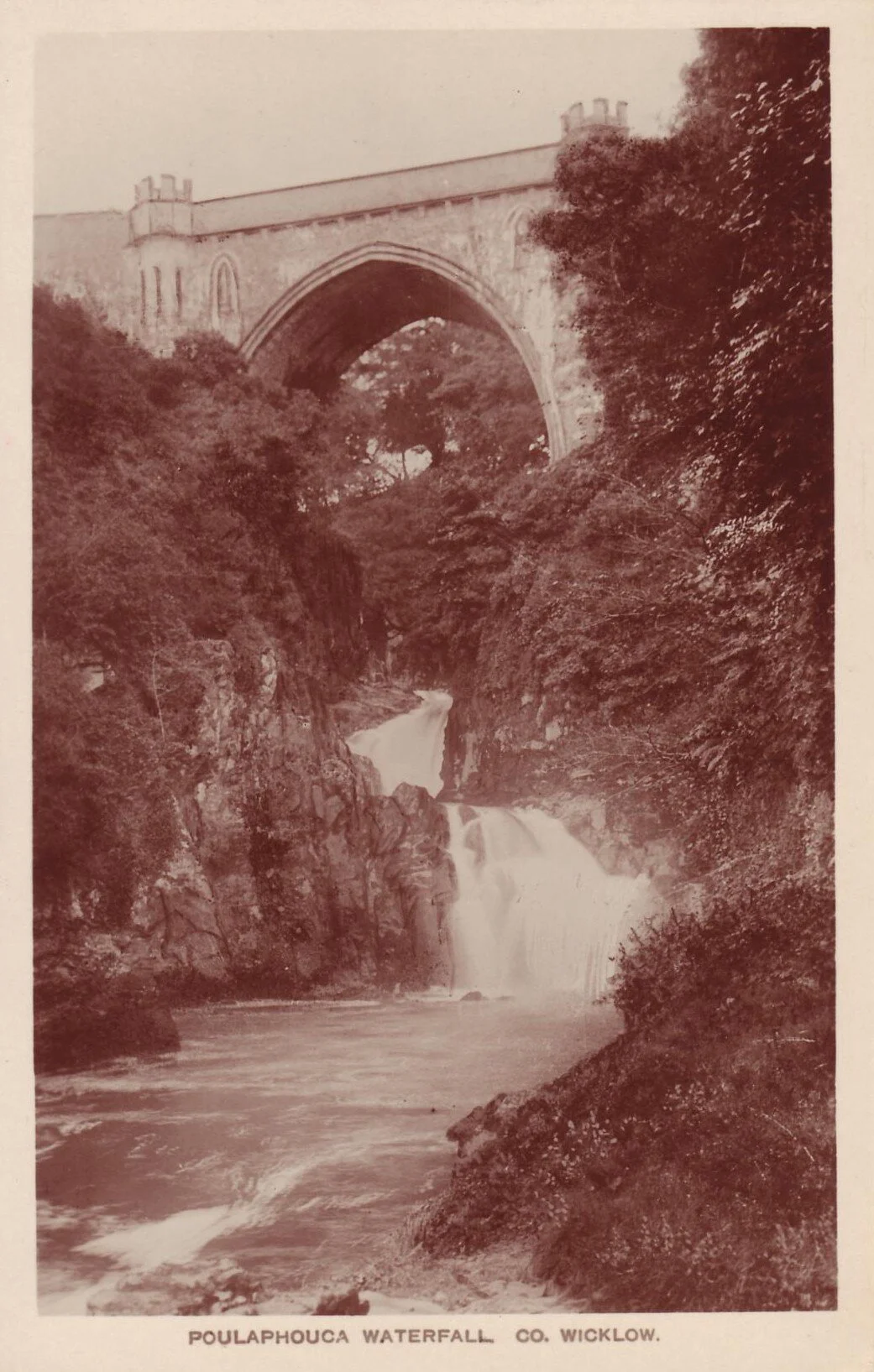

The Poulaphouca waterfall. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

The fantasy supplies somewhat hazy memories of Bloom’s adolescence and a school field trip to Poulaphouca waterfall. It seems that Bloom pleasured himself “in the open air” (15.3344). He explains it as a sacrifice “to the god of the forest” (15.3353), notes the various arousals of springtime, cites the effect of peeping on a woman in her bathroom (is that an excuse?), resorts to blaming a “demon” (15.3359), and eventually says that he was “simply satisfying a need” (15.3365) that wasn’t being fulfilled by the girls his age, who apparently didn’t find him attractive. As we continue to learn Bloom’s most intimate secrets and plumb the depth of his subconscious, it may be worth noting that we now perhaps know Mr. Bloom more completely than it might be possible to know a real person.

The scene shifts to Howth Hill, the site of Bloom’s proposal to Molly, as remembered in “Lestrygonians” (see 8.900-16). Bloom borrows language from the “Sirens” episode (“Done. Prff!” (15.3390)), and the Nymph finally answers Bloom’s question regarding the private parts of goddesses. The hold of the fantasy begins to recede as voices from the musicroom blend with the imaginary voices. As Bloom emerges from the Bello daymare, he stands more upright, representing a change in posture and in attitude. As evidence of this change and its real-world effect, the back button on his pants pops off and says, “Bip!” (15.3441). Newly assertive and “composed” (15.3483), Bloom has “broken the spell” (15.3449) of his guilt over Rudy’s death and subsequent deficiencies. Heroically, he is able to endure and overcome this intense shame as well as these frank reckonings with his life’s failures and most mortifying moments.

Reflective of this shift in his mentality, Bloom asks Zoe to return his potato. Not a huge deal in the grand scheme of things, but he’s standing up for himself, claiming what’s rightfully his. It’s something.

Bella attends to the business side of things, asking “who’s paying here?” (15.3529). Each prostitute charges 10 shillings for the pleasure of their company (equating to roughly $150 in today’s money – see my “Money in Ulysses” page for a refresher on this old British system of currency). Stephen is exceedingly sloppy in the transaction, initially giving Bella a £1 banknote, which would pay for him and Lynch. When Lynch calls for Dedalus to cover him, Stephen unnecessarily gives Bella a half sovereign coin (worth 10 shillings). Bella is confused by this overpayment, and Stephen apologizes and “fumbles again and takes out and hands her two crowns” (15. 1545-46); a crown coin is worth 5 shillings. So, Stephen has just given Bella an additional 10 shillings for a grand total of 40s (£2) in remittance. He has handed over roughly $600 in today’s cash. Keeping in mind that Stephen received £3 12s from Deasy this morning (see 2.209-22) for a month’s teaching salary, this level of carelessness is astounding. Stephen returns to the pianola and reprises his fox riddle from “Nestor,” leaving the others to sort out the financial confusion. Clever Bloom “quietly lays a half sovereign on the table” (worth 10s, bringing the total paid to 50 shillings) and then “takes up the poundnote” (worth 20s, thus bringing the total paid down to 30s) and states simply “three times ten. We’re square” (15.3583-84). Point Bloom.

Bloom returns the rescued poundnote to Stephen and suggests that he “had better hand over that cash to [Bloom] to take care of” (15.3601). Stephen muses on his riddle, and Bloom rounds up what he owes Stephen back by a penny. Stephen mourns that his favorite whore, Georgina Johnson, “is dead and married” (15.3620). Stephen is too drunk to light his cigarette (always a good hint to call it a night), and then he drops it on the floor. Bloom, emboldened and fatherly, tells Stephen, “Don’t smoke. You ought to eat” (15.3644). Zoe begins reading palms. Lynch slaps Kitty’s bottom like a “pandybat” (15.3666), which triggers Stephen to have a brief fantasy of the unjust punishment he received from Father Dolan at Clongowes (as portrayed in A Portrait). Mild Father Conmee from “Wandering Rocks” and A Portrait then appears and intervenes on Stephen’s behalf. Zoe continues reading palms, and Bloom identifies his scar from the injury Bloom’s father recalled earlier in this episode (15.274). Stephen winces and observes that he “hurt [his] hand somewhere” (15.3720-21), which might be psychosomatic pain from the fantasy of Father Dolan’s flogging, or it might be related to a real scuffle with Buck at Westland Row Station just over an hour ago. The whores giggle in the background, and the barmaids and the boots from “Sirens” appear in the book’s imagination.

The sixth sustained fantasy begins with Blazes Boylan arriving with Lenehan. These two assholes make lewd comments to one another before Boylan calls to Bloom, treats him like a servant, and casually cuckolds him (he even invites Bloom to watch through the keyhole). Bloom has been actively suppressing this scene all day, but it tumbles out of his subconscious here in the most disturbing and degrading way possible.

The whores continue to giggle. A crossfade occurs as Bloom and Stephen both “gaze in the mirror” (15.3821) and the image of Shakespeare appears and coexists in the reflection of both men. Bloom, like Shakespeare, is a cuckold; Stephen, like Shakespeare, is a troubled artist. Paddy Dignam’s widow appears with her children. Martin Cunningham’s face appears in the mirror and “refeatures Shakespeare’s beardless face” (15.3854-55). Bloom made this connection between Cunningham and Shakespeare during the carriage ride in “Hades” (see 6.345).

We return to reality with Stephen blaspheming, which Bella won’t allow in her brothel. The whores ask him to speak some French. He speaks drunken bawdy gibberish in French syntax. The prophetic dream he remembered in “Proteus” (see 3.365-69) finally clicks: “It was here. Street of harlots. […] Where’s the red carpet spread?” (15.3930-31). Recognizing that Stephen is losing his shit, Bloom tries to calm him with fatherly cautioning even as Stephen proclaims that he has soared to freedom beyond any sort of paternalistic forces. At Stephen’s combative cry, a fantasy begins as his real father, Simon, “swoops uncertainly through the air, wheeling […] on buzzard wings” (15.3945-46). A scavenging vulture, Simon encourages Stephen to win for the family and “keep our flag flying” (15.3948). Stephen becomes the fox from his riddle, “having buried his grandmother” (15.3952-53) (i.e., his mother), pursued by a “pack of staghounds” (15.3954). This race becomes a rerunning of the Gold Cup with Mr. Deasy riding a horse called Cock of the North.

(Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

Back to reality. Private Carr, Private Compton, and Cissy Caffrey discordantly sing “My Girl’s a Yorkshire Girl” as they pass the window of Mrs. Cohen’s; Zoe, a Yorkshire girl, goes to the pianola, puts on this song, and gets everyone dancing (except Bloom, who “stands aside” (15.4030). The dancing master Denis Maginni appears dressed to the nines and instructs the other dancers. Stephen, Lynch, Florry, Zoe, and Kitty twirl and waltz. Stephen calls for a “pas seul” (15.4120) (a solo dance), and busts a move: he “frogsplits in middle highkicks with skykicking mouth shut hand clasp part under thigh” (15.4124-25). Try it. I dare you.

Dizzy and lightheaded from this exertion, Stephen hallucinates the appearance of his dead mother, “her face worn and noseless, green with gravemould” (15.4159). Since the very beginning of the novel (see 1.103-110), Stephen has been haunted by the images of her death, his guilt for refusing to pray for her on her deathbed, and her appearance to him in a nightmare. Of course Buck Mulligan shows up to twist the knife. Stephen’s mother implores him to pray and “repent” (15.4198) and expresses her eternal motherly love for him. This imaginary encounter has clearly affected Stephen in reality, as Florry notes that “he’s white” (15.4208). Back in the hallucination, Stephen’s mother warns him of “the fire of hell” (15.4212) and to “beware God’s hand” (15.4219). Perhaps representative of God’s hand, “a green crab with malignant red eyes sticks its grinning claws in Stephen’s heart” (15.4220-21). Horrorstruck and “strangled with rage,” Stephen yells “Shite!” and “Non serviam!” (15.4223, 4228), echoing Lucifer’s refusal to serve God. The others in the brothel are alarmed, and Florry rushes out to get Stephen some cold water. Stephen “lifts his ashplant high with both hands and smashes the chandelier” (15.4243-44) before flying from the room and out into the street.

Bella grabs Bloom and demands 10 shillings in compensation for the damage to the lamp. Bloom calmly takes a look and discerns that “there’s not sixpenceworth of damage done” (15.4290-91). Bella threatens to call the police, but Bloom offers a variety of pragmatic reasons (some true, some false) to handle this situation discretely. Finally, he uses his knowledge that Bella’s son is a student at Oxford, which he learned from Zoe when he arrived at the brothel (15.1289). Bella is startled. Bloom leaves a shilling “for the chimney” (15.4312-13) of the chandelier and hurries out to find Stephen. As he is leaving Mrs. Cohen’s, he “averts his face” (15.4320) from three other men, including Corny Kelleher and perhaps Blazes Boylan, who are on their way into the brothel. Bloom, carrying Stephen’s abandoned ashplant, is pursued (not really) by a large crowd of people from his past and from this day who are antagonistic toward him or at least suspicious of him.

Think Private Carr. (Photo provided courtesy of JoyceImages.com)

Bloom comes upon a crowd surrounding a confrontation between Stephen and Private Carr. It seems Stephen was speaking with Cissy Caffrey when the soldiers returned from taking a leak. Private Carr accuses Stephen of insulting Cissy, and Stephen seems heedless of the danger as he drunkenly pontificates. Private Compton eggs his buddy on to “biff him one” (15.4392). Carr threatens to “bash in [Stephen’s] jaw” (15.4411). Stephen teaches the definition of a rhetorical device. Not only is Stephen hammered to the point of obliviousness, but he is at his core a passivist who “detest[s] action” (15.4414). Bloom makes his way through the crowd and attempts to extricate “professor” (15.4424) Dedalus from the situation. Stephen can barely stand up.

Gesturing toward his mind, Stephen explains to the redcoats that “here it is I must kill the priest and the king” (15.4436-37). Poor choice of words. Carr takes this statement as a direct threat against the King of England, who the Arranger promptly conjures to officiate the fight. Bloom tries to appeal to the privates, explaining that Stephen is drunk on absinthe and “a gentleman, a poet” (15.4488). The privates “don’t give a bugger who he is” (15.4493)…plus they are Neanderthals.

As Bloom continues to coax Stephen to leave, the text produces a slew of quick figurations of the Irish-English conflict. Carr continues to taunt, and Stephen exclaims “O, this is too monotonous!” (15.4568) and “tries to move off” (15.4575). He has also forgotten where his money went. The privates accuse Stephen of being a proBoer, but Bloom retorts that the Royal Dublin Fusiliers fought for Great Britain in South Africa, which prompts a fantasy of Major Tweedy (Molly’s dad) appearing and confronting the Citizen. Carr seems determined to hit Stephen, and Cissy seems excited by the prospect of being fought over. Carr offers unwitting puns about his “bleeding fucking king” (15.4645) – King Edward VII was a hemophiliac (bleeding) and a womanizer (fucking). Bloom implores Cissy Caffrey to intervene and pacify the situation. She tries…but too little, too late. After some imaginary hysteria, Bloom then pleads with Lynch to help get Stephen away from this danger. Lynch can’t be bothered and slinks off with Kitty. As he leaves, Stephen calls him “Judas” (15.4730) – but isn’t Lynch more of a Peter denying Jesus? Anyhow, Bloom again tries to get Stephen away, Cissy forgives Stephen for insulting her and tries again to get Carr away. Just as you think it might end peacefully, Private Carr “rushes towards Stephen, fist outstretched, and strikes him in the face” (15.4747-48). Stephen collapses, out cold.

The first and second watch return from the beginning of the episode to investigate the incident. Bloom gets over his skis a little bit and instructs the watch to “take [Carr’s] regimental number” (15.4788-89). They don’t like being bossed around. Compton realizes that Carr should leave the scene to avoid getting in trouble with his superior officer, and Bloom realizes that Stephen might get arrested. Just in time, Corny Kelleher comes upon the scene, and Bloom fills him in. Kelleher, known by the police to be a valuable informant, calls off the watch. Phew! Richard Ellmann explains the role of “Corny Kelleher, the undertaker, whose symbolical presence probably implies the burial of the old Stephen” (Ellmann 146). We will see in the remaining episodes of the novel whether indeed a new Stephen arises from this collapse.

Crisis averted, Corny and Bloom now somewhat awkwardly have to explain their respective presences in Nighttown. Corny claims to have been drinking with two other guys who “were on for a go with the jolly girls” (15.4863), but Corny refrains from joining them in the brothel because he thankfully is married and “ha[s] it in the house” (4870). One of these two guys Corny was with reportedly lost £2 on the Gold Cup, as did Boylan…so Bloom and Boylan might have walked right past each other at the entrance to Mrs. Cohen’s. For his part, Bloom offers a totally bogus and implausible explanation.

What to do now? Thinking Stephen lives in Cabra, Corny offers to give him a ride home in his carriage. When he learns that Stephen has been staying all the way down in Sandycove…“ah, well, he’ll get over it” (15.4896). Bloom also realizes that he doesn’t really have an endgame, and now he’s stuck holding the bag of a knocked out, passed out 22 year old he scarcely knows. As Corny departs in the car, he “sways his head to and fro in sign of mirth at Bloom’s plight”; “Bloom shakes his head in mute mirthful reply” (15.4910-13). You can only laugh.

Mr. Bloom, characteristically caring and kind, bends down to shake Stephen’s shoulder, trying to rouse him. Stephen speaks a few fragments and murmur-sings a few words from “Who goes with Fergus?” – Yeats’s song is still in Stephen’s mind from this morning, when he remembers singing it to his mother on her deathbed. Stephen’s recollection of his mom’s response, “for those words Stephen: love’s bitter mystery” (1.252-53), predicts this moment and Bloom’s unexpected act of love. Because Bloom does not recognize Yeats’s poem, he misunderstands “Fergus” and “white breast” to refer to “a girl” (15.4950); he thinks in a fatherly way that a stable relationship would be the “best thing could happen him” (15.4950). Standing guard over Stephen, Bloom’s psyche conjures a beautiful fantasy of Rudy, now eleven years old, reading Hebrew, “smiling, kissing the page” (15.4959-60). This ending is lovely, poignant, and emotionally affecting. Go ahead, you can cry if you want.

As you might imagine, scholars have lots of opinions on this concluding fantasy. Richard Ellmann claims that “Here, out of love for his dead child, [Bloom] does more than remember, he reshapes Rudy’s misshapen features and raises him from the grave (Ellmann 149). On the other hand, Hugh Kenner suggests that “Rudy, we may deduce, does not appear to Bloom at all. [He] appears to us, a gratuitous pantomime transformation supplied by the second narrator to resolve and terminate the episode, and to serve as notation for the empiric truth that Bloom’s next thoughts are paternal ones” (Kenner, Voices, 93). If Kenner is correct, then the vision of Rudy allows the Arranger “to project one of Bloom’s deepest wishes at a strategic moment in the text [and] to feel where the climax would have been in a more conventional novel” (Lawrence 160-61). Clearly, “Circe” is the most unconventional episode in an exceedingly unconventional novel, so you have license to think and feel what you like about Rudy’s appearance here at the end.

After recycling these hundreds of elements from elsewhere in Ulysses as he composed “Circe,” Joyce expanded his understanding of this novel’s potential as “a kind of encyclopedia” (Selected Letters 271). He began revising the rest of the book accordingly, arranging little snippets of interrelated detail throughout the previous episodes into an intricate network of minor motifs that accumulate and aggregate in the careful reader’s awareness. “Circe” serves as an absurd but cathartic outpouring of Ulysses thus far. Having gotten all that out of our systems, we are ready for the episodes Joyce called the “Nostos,” the return.

Works Cited

Beach, Sylvia. Shakespeare and Company. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Byrnes, Robert. “Weiningerian Sex Comedy: Jewish Sexual Types Behind Molly and Leopold

Bloom.” James Joyce Quarterly. Vol. 34, No. 3. University of Tulsa, 1997.

Ellmann, Richard. Ulysses on the Liffey. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

--- James Joyce. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Gifford, Don, and Seidman, Robert J.. Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. University of

California Press, 2008.

Groden, Michael. Ulysses in Progress. Princeton University Press, 1977.

Hayman, David. Ulysses, the Mechanics of Meaning. University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Joyce, James. Letters of James Joyce: Volume I. Edited by Stuart Gilbert. Viking Press, 1966.

Kenner, Hugh. “Circe.” James Joyce's Ulysses: Critical Essays. Ed. Hart, Clive, and David Hayman.

University of California Press, 1977.

--- Joyce’s Voices. University of California Press, 1978.

--- Ulysses. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Lawrence, Karen. The Odyssey of Style in Ulysses. Princeton University Press, 1981.

Sultan, Stanley. The Argument of Ulysses. Wesleyan University Press, 1988.