Episode 2: Nestor

The “Nestor” episode depicts Stephen at work as a teacher a private boys’ school in Dalkey, which is about a 20 minute walk south from the Martello Tower. We know Stephen departed the tower no sooner than 8:45 am (the bells chimed three quarters past the hour at the end of “Telemachus”), so he presumably arrives a few minutes past 9:00 am. He is late to work.

In The Odyssey, Telemachus leaves Ithaca in search of news of his long lost father. Under the guidance of Athena, he first visits Pylos, the kingdom of Nestor, a wise old man and former comrade of Odysseus’s.

The narrative joins Stephen around 9:40 am in the midst of his lesson. Stephen’s teaching is uninspired. He quizzes the boys on memorized historical facts related to the costly victory won by the Greek King Pyrrhus over the Romans at Asculum. By Stephen’s need to “glance at the name and date in the gorescarred book” (2.12-13), we gather that he is unprepared for class…we’ve all been there, students and teachers alike.

A recreation of Stephen’s walk from the Tower in Sandycove to Mr. Deasy’s School in Dalkey.

As Stephen teaches, his inner monologue reveals the background activity of his remarkable mind: he thinks of William Blake’s characterization of history as romanticized and “memory fabled” (2.8), he wrestles with Aristotle’s ideas regarding history and events as the only possible outcomes (“was that only possible which came to pass?” (2.52)), and he vividly imagines General Pyrrhus leaning on a spear and speaking to his officers on “a hill above a corpestrewn plain” (2.16). We will spend more time with Stephen’s layered and erudite thoughts during this episode, so you might want to have the Gifford handy if you want each of his allusions explained. Here, I’m more interested in helping you build momentum and confidence as we continue to gain a foothold in this beautiful beast of a novel.

The students laugh at Armstrong, a boy who seems more interested in sneaking bites of his figrolls than learning his history, and Stephen silently acknowledges his “lack of rule” (2.29) in the classroom. Perhaps he isn’t delivering an educational experience worthy of the tuition “fees their papas pay” (2.29). Stephen’s cleverness in defining a pier as a “disappointed bridge” (2.39) goes right over his students’ heads, but he intends to remember this witticism “for Haines’s chapbook” (2.42). At this thought, he registers some self-loathing for his willingness to play the role of “a[n Irish] jester at the court of his [English] master,” merely an intellectual entertainer seeking his “master’s praise” (2.45-46).

Stephen abandons the history lesson in favor of poetry. A boy recites a section of Milton’s “Lycidas,” which reinforces the drowning motif established in “Telemachus.” Stephen remembers the year he spent in Paris reading Aristotle in French: “the studious silence of the library of St. Genevieve where he had read, sheltered from the sins of Paris, night by night” (2.69-70). This image of Stephen contentedly surrounded by other “fed and feeding brains” (2.71) contrasts with the suffocating atmosphere of the tower (and perhaps Dublin in general) for this young man. Prior to dismissing the boys to get ready for field hockey, Stephen concludes his lesson with a nonsensical riddle, the answer to which is “the fox burying his grandmother under a hollybush” (2.115). This suggests Stephen’s feelings of culpability for his own mother’s death. Stephen then gives extra math tutoring to a struggling student named Cyril Sargent. Looking at the “lean neck” and “tangled hair” of the “ugly” boy (2.139), he muses on the love and protection young Sargent has received from his mother. Echoing Cranly from A Portrait, Stephen reflects that a mother’s love may be “the only true thing in life” (2.143). He thinks of the Irish Saint Columbanus’s mother, over whose “prostrate body” (2.144) the priest had to step as he departed for his missionary work “grievously against her will” (Gifford 33). His mind returns to his own mother and her haunting appearance to him in a dream with “an odour of rosewood and wetted ashes” (2.145-46). Stephen then imagines the fox from his riddle: “with merciless bright eyes [he] scraped in the earth, listened, scraped up the earth, listened, scraped and scraped” (2.149-50). The repeated scraping and listening might signify that the fox, after “burying his grandmother,” is now trying to exhume her, listening for signs of life. Stephen, after “merciless[ly]” refusing his mother’s dying wish, wants to bring her back to life.

As Stephen works the math problem for Sargent, he recalls Mulligan’s taunt that “he proves by algebra that Shakespeare’s ghost is Hamlet’s grandfather” (2.151-52). Stephen also sees a bit of his childhood self in Cyril’s “sloping shoulders” and “gracelessness” (2.168). They wrap up the extra help session, and Stephen dismisses Cyril to join his classmates at field hockey (an English sport, indicating Headmaster Deasy’s politics).

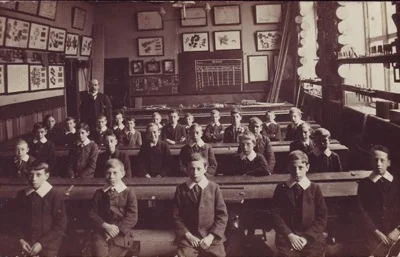

Mr. Deasy’s School (photo courtesy of Marc Conner)

We meet Mr. Deasy, the correspondence to King Nestor, with his “angry white mustache” (2.188) and “illdyed head” (2.197-98) in the field sorting the boys into teams and getting the game underway. He tells Stephen to wait for him in his study for their “little financial settlement” (2.207). Deasy enters and pays Stephen his monthly salary of £3, 12s in two £1 notes, a sovereign coin (also worth £1), two crown coins (worth 5 shillings each), plus two shilling coins. This wage is roughly equivalent to $1,000 in today’s spending power. He collects his payment with “shy haste” (2.223-24), and Deasy advises him to organize and save his money in a “little savingsbox” (2.218) machine like his. After prodding himself to “answer something” (2.231) to Deasy’s unsolicited advice, Stephen replies that his savingsbox “would be often empty” (2.232). Deasy continues to lecture him on financial prudence, citing Shakespeare: “put but money in thy purse” (2.239). Of course, Stephen recognizes that Deasy has taken this line completely out of context – in Othello, the treacherous Iago says this phrase repeatedly as he manipulates Rodrigo. Deasy’s knowledge of Shakespeare (and most other things) is superficial. Deasy also demonstrates that he is a West Briton, an Irish supporter of England, as he continues to espouse financial discipline as an English virtue, claiming that “I paid my way” (2.251) is the “proudest word you will ever hear from an Englishman’s mouth” (2.244-45). Stephen’s inner monologue silently mocks Deasy (“Good man, good man” (2.252)) before cataloguing his own debts owed to at least ten people around town, totaling over £25 – roughly $7,500 today. In the face of this mountain of debt and in youthful irresponsibility, Stephen thinks that “the lump” of money he just crammed into his pocket is “useless” (2.259) to even begin paying off what he owes…plus we know that he plans to go drinking this afternoon.

Deasy then shifts focus to the history of the Irish independence movement, making assumptions about Stephen’s politics and generally striking the wrong chords. You might take a look at these pages and note how little Stephen says in this conversation. Deasy then asks a favor: he has written a letter on the topic of foot and mouth disease, a viral contagion that can decimate entire populations of cattle, and he’d like for Stephen to arrange for its publication in a Dublin newspaper. As Deasy finishes copying the letter on his typewriter, Stephen looks around at the pictures of famous horses adorning Deasy’s walls. He recalls a day of horserace gambling with Cranly. He hears shouts and a whistle from the field hockey game outside, leading his mind to conflate the “battling bodies” (2.314) of the boys playing sports with the “slush and uproar of battles, the frozen deathspew of the slain, a shout of spearspikes baited with men’s bloodied guts” (2.317-18). In this passage, we may find “barely disguised World War I imagery – bayonets, grenade blasts, mud, trench warfare” (Epstein 23). When combined with the earlier image of Pyrrhus surveying “a corpsestrewn plain” (2.16), we might be reminded that the Great War was raging around Joyce as he composed “Nestor” in 1917 in neutral Switzerland. Bob Spoo has pointed out that many of the boys Stephen has just taught would have been sent to the trenches.

Deasy finishes copying the letter and hands both copies to Stephen, who skims it to get the gist that foot and mouth disease threatens the export of Irish cattle and that Deasy’s cousin in Austria claims that veterinarians there have developed a cure. Deasy tells Stephen that he has encountered difficulties in getting the government’s attention on this issue, blaming conspiratorial intrigues and the covert influence of the Jews. Deasy’s anti-Semitism, similar to Haines’ in the previous episode, imagines Jews operating in the shadows and signaling “a nation’s decay” (2.348): “As sure as we are standing here the jew merchants are already at their work of destruction” (2.349-50). Deasy’s anti-Semitism reinforces the hostile social context into which Joyce will place Mr. Bloom, whom we will meet in the novel’s fourth episode. Stephen silently recalls a memory of Jewish businessmen in Paris. While this passage includes derogatory stereotypes, it seems that Stephen expresses an overall attitude of sympathy, especially since he immediately speaks up to defend Jewish merchants as being no different from their gentile counterparts. Deasy retorts that “they sinned against the light” (2.361), alluding to the Christian belief that the Jewish people are guilty of deicide, the murder of Jesus/God. The idea of the mythological Wandering Jew makes its first appearance in the novel, foreshadowing Bloom’s 18 hours of wandering around Dublin. You can be sure that Joyce will put his own spin on this old trope.

In response to Deasy’s assertion that the Jews “sinned against the light,” Stephen asks “Who has not?” (2.373), literally dropping Deasy’s jaw. Stephen’s inner monologue wonders “is this old wisdom?” (2.376), indicating the failure of Deasy/Nestor to serve as the father figure Stephen/Telemachus seeks. Explaining Deasy’s shortcomings, Richard Ellmann explains that “what he offers to Stephen, as worldly wisdom, is archaic conservatism in politics, and conserved wealth in finance – kingdoms of the past and of the future. Stephen seeks a different kingdom, that of the ‘now, the here’” (Ellmann 21). As such, Stephen offers his rebuke of history, saying that “history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake” (2.377). He means both the nightmare of Ireland’s history of subjugation as well as his personal inability to escape the haunting history of his mother’s death. Deasy proposes a Victorian platitude that “history moves toward one great goal, the manifestation of God” (2.381). However, “God to Stephen is not the final term in a process but rather a ‘shout in the street,’ some totally unexpected and unforeseeable manifestation” (Epstein 22). Stephen, “shrugging his shoulders” (2.386), accepts his incompatibility with Deasy. Proving this point, Deasy spews a misogynistic diatribe, scapegoating females figures from the Bible (Eve), Homer (Helen), early Irish legend (12th century King Dermot MacMurrough’s wife), and contemporary Irish politics (Kitty O’Shea). Stephen is done here. He makes ready to leave.

Deasy is wrong on many things, but he is correct about Stephen’s unhappiness and in forecasting that Stephen “will not remain here very long at this work” (2.401-02). Stephen doesn’t argue, claiming that he’s “a learner rather” than a teacher (2.403). He silently questions what more he will learn here – with Deasy specifically and in Dublin generally. Deasy offers an appropriate (if trite) pearl of wisdom, saying “To learn one must be humble. But life is the great teacher” (2.406-07). Proud, insecure young Stephen might do well to consider this advice, but we can’t blame him for dismissing Deasy in the context of his intellectual vapidity, anti-Semitism, and misogyny. Yet, “still [Stephen] will help him” (2.430) with the publication of his letter, imagining that Buck will have a new mocking label for him: “the bullockbefriending bard” (2.431).

As Stephen walks away from the school, Deasy calls and hustles after him to jab a final anti-Semitic barb: “Ireland, they say, has the honour of being the only country which never persecuted the jews […] Because she never let them in” (2.437-38, 42). The revolting description of Deasy’s “coughball of laughter leap[ing] from his throat dragging after it a rattling chain of phlegm” (2.443-44) emphasizes the novel’s rejection of prejudice.

Stephen leaves the school to catch a northbound train from the Dalkey station. We will next see him walking along Sandymount Strand, enjoying some time alone with his own thoughts.

Works Cited

Ellmann, Richard. Ulysses on the Liffey. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Epstein, E. L. “Nestor.” James Joyce's Ulysses: Critical Essays. Ed. Hart, Clive, and David Hayman.

University of California Press, 1977.

Osteen, Mark. The Economy of "Ulysses": Making Both Ends Meet. Syracuse

University Press, 1995.

Spoo, Robert E. “‘Nestor’ and the Nightmare: The Presence of the Great War in Ulysses.” Twentieth

Century Literature, vol. 32, no. 2, 1986, pp. 137–154. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/441379.

Accessed 4 Aug. 2020.